This subject has come up partly in response to an email question I received awhile back (about a prior blog post) and partly from being in the audience recently for Jim Providenza’s excellent clinic on the topic. But when I thought about how I choose routings for the waybills on my layout, I realized I use a part of the process Jim didn’t address. This post explains it.

Prototype waybills contain a section in which the route of the loaded car is specified, and it is to be in route order. Here’s that instruction on the waybill, all by itself, so you can see clearly what is wanted.

I have visited layouts at which this is rather roughly filled in, with railroads and no junctions, but most modelers know the national railroad network well enough to at least guess at junctions. And some routings can be easily guessed, for example, oranges from California to Chicago, very possibly Santa Fe all the way (except for perhaps some other railroad making delivery in Chicago). We can also choose routes in which the originating road moves the car as far as possible on its own rails, and this would be realistic if a railroad agent chose the routing.

But it’s important to realize that, after a series of hard-fought court cases, it was determined that the shipper had the absolute right to choose routing of his cargo, regardless of whether it benefited the originating railroad or not. The shipper might choose what was believed to be the fastest route (not necessarily the shortest); the route using railroads with the best service; or a route benefiting a railroad he wished to use, even if not the most direct. The only restriction was that it had to be an “approved route,” though there were so many of these that it would require ingenuity to choose a non-approved route, at least east of the Mississippi River.

There is a well-known story about a shipper of perishables in Southern California, whose packing house had a spur served by the Santa Fe. But he had had numerous disputes over charges and service with the local Santa Fe officials, and accordingly he routed his carloads about two miles on the Santa Fe, to the nearest Southern Pacific junction, and then onward via SP, followed by any railroad except the Santa Fe. This was entirely within the rules.

This story amplifies my point that the routing actually chosen by a shipper for a particular cargo might not be the apparently logical one. And prototype waybill examples bear this out, with many routings not at all obvious from the map. But not just any map. We need the right sort of map.

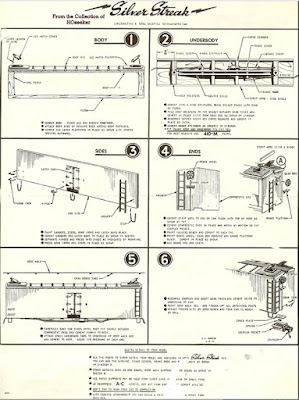

One place to find these is with a railroad atlas, that is, a set of railroad maps, not a highway map. At times, Kalmbach has reprinted some Rand McNally atlases of this kind, and these can usually be found for sale by on-line booksellers. The most detailed one is the 1928 atlas, with the drawback that many of the smaller railroads in it were later merged into other roads, or abandoned. I still like it for its detail. Its cover is shown below.

For some purposes, one might prefer a later atlas, for the reasons I mentioned, and indeed Kalmbach did reprint a 1948 version. Some of the detail was removed, but generally it is quite useful in its own right, relative to the 1928 atlas. Here’s its cover:

So what do I do in figuring out a routing? Let me choose an example process. Let’s say that I want to choose an inbound load to one of my 1953 layout industries. A great source of industry information is the OpSig industry database (see: https://www.opsig.org/Resources/IndustryDB ), but even more information of this kind is available in reprinted Shipper Guides for individual railroads (the ones currently available at Rails Unlimited can be seen here: https://railsunlimited.ribbonrail.com/Books/shippers.html ).

I’ll choose a load inbound to my Caslon Printing Co. in East Shumala on my SP layout. There was a national market in printers’ equipment and supplies, so I looked for sources in the recently-printed B&O Shipper Guide (see my review at: https://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2024/01/another-excellent-shippers-guide.html ). On page 468, under Printers and Printers’ Supplies, I found Ace Electrotype Co., offering engravers’ supplies. They were located on a B&O siding, so the B&O would be the originating railroad and would write the waybill on a B&O form.

How would a shipment like this move to the west coast? A majority of such shipments moved through Chicago and then via the Overland Route to SP rails in Ogden, Utah. Since B&O did serve Chicago, they might have wanted this load to move to Chicago on their rails. But the shipment is really going to Southern California, and the traffic manager at Ace Electrotype might choose instead to route the car to St. Louis (also via B&O), for transfer to the Cotton Belt, thence through Texas via T&NO to SP rails at El Paso. Either route is reasonable.

But that traffic manager may have a friend (or sales colleague, who sends him a bottle of Scotch every Christmas) at the Western Maryland, so he may choose WM westward. Then the B&O hands the load to the WM in Baltimore, and it moves through Connellsville, PA to the P&LE, which would hand off to New York Central in any one of several places. At that point, the car can move to either St. Louis or Chicago as described above. And in St. Louis, the car might be transferred to the Rock Island, which could take it to SP rails in Tucumcari, New Mexico, instead of Cotton Belt. And so forth.

The foregoing examples are major railroads and major cities. Where the railroad atlas really shines is for a small town, either as origin or destination. What railroad(s) served New Bern, North Carolina? or Holland, Michigan? Brownwood, Texas? Billings, Montana? Answers are easy with a railroad atlas.

I’ll continue with some details, and example of waybills I’ve generated this way, in a future post.

Tony Thompson